Raw Mango’s story began in 2006, with one textile. Till today, Chanderi is our happy place.

An old historical town located in the district of Ashoknagar of northern Madhya Pradesh, Chanderi rose to prominence in the 11th Century. Around this time the region also became one of the most important trade routes in India, given its proximity to the ancient ports of Gujarat, Malwa, Mewar, Central India and Deccan. The region has a multicultural population, all of whom are a part of its handloom industry. Textile has always been an essential part of Chanderi and over the last 500 years the region has produced saris, furnishings, odhanis, pagdis and other garment fabric, especially for the Royal families in India. It is said that the fabric was introduced by Lord Krishna’s cousin Shishupal. In the Maasir-i-Alamgiri, it is stated that Emperor Aurangzeb ordered the use of a cloth embroidered with gold and silver to make a khilat (a ceremonial robe given to a senior).

Traditionally, garments were made using the finest cotton yarn of up to 200 count and yarn was hand spun on Charkhas by a local tribe called ‘Katia’. The other thread made of pure gold & silver called Zari was used for making borders and butis was being imported from France. The fabric being produced was categorized as 100% cotton, and unbleached grey yarn was used in the body warp & weft border. In 1936, 13/15 denier raw silk yarn came from Japan and was used in Chanderi sarees for the first time, since then the silk yarn is used in warp and cotton yarn for weft and this construction of fabric became very popular and is traditionally known as ‘Chanderi fabric’.

Chanderi is a semi-sheer soft, airy textile with a luster given its cotton/silk weave. Its lightness is famed and described as ‘bunni hui hawa (woven air). Chanderi is famous for its extremely fine silk warp products of untwisted 16-18 denier. Weft has the option for using 120s count cotton or 22-23 denier twisted silk, locally called "katan" or organza.

Sanjay became engaged with a small project in Chanderi in 2008, encountering Chanderi for the first time. Once this happened, he didn’t see any reason in pursuing further studies in London. It was during this textile project that he was motivated to think more deeply about why Chanderi & handloom were in such a crisis, why didn’t women want to wear saris anymore, and how he could investigate and question the current perspective on it? It was at this point he met Bhagwan Das and Kishanal, who remain part of the team today. Our journey began over a cup of chai in Chanderi and has turned into a decade-long relationship wherein, our work together sustains each other.

“मैं चंदेरी का रहने वाला हूँ। मेरे पूर्वजो से ही बुनाई का काम चल रहा है और मैंने बुनाई का काम अपने माता पिता से सीखा है। लगभग २५(25) सालों से मैं बुनाई का काम कर रहा हूँ। चंदेरी सिल्क का काम कई बार मंदा और तेज़ रहा है। जब २००७(2007) में संजय जी चंदेरी आये थे तब उन्होंने सैंपलिंग का काम शुरू किया था और फिर उन्होंने काम शुरू करने के लिए कुछ सैंपल बनवाये और तब से चंदेरी के काम में उछाल आया। दस साल पहले मजदूरी १०० रूपए(100 INR) प्रतिदिन के करीब थी और अब मजदूरी ५०० - ७०० रूपए (500-700 INR) प्रतिदिन हो गयी हैं। इस से मजदूरों की आय में सुधार आया और संजय जी ने चन्देरी के काम में अपना पूरा योगदान दिया है। उन्होंने चंदेरी के व्यवसाय को बढ़ाने के लिए चंदेरी बुनकरों को काम दिया हैं और आगे भी करते रहेंगे। चंदेरी बुनकरों की तरफ से संजय जी का धन्यवाद। आगे भी चंदेरी का काम इसी प्रकार चलता रहे ये उम्मीद करते है।”

- Bhawan Das Kohli.

Sanjay’s intervention to shift from pure cotton Chanderi to a silk cotton fabric led to a major change within the textile- it is neither dull like cotton, nor shiny like silk. Instead it has beautiful, balanced lustre and a lovely drape, perfect for India’s tropical climate. Over the last 14 years our work in Chanderi has made us understand the impact time and sustained effort can make, the various meanings of ‘revival’ and most importantly, how growth can be mutually beneficial.

Traditionally, weavers are inspired by the architectural remains of the Mauryan and Mughal empires in Chanderi, along with nature and its abstract forms are reflects in the motifs and designs of nal pherwa, dandidar border, chatai, jangla, bundi, ganga jamuni, ashrafi booti etc. Introduction of motifs in what used to be a predominantly plain woven piece of fabric with thin borders proved to be tricky as the loom can only accommodate certain techniques of weaving, given the limited use of specific materials and design vocabulary. Our success with this contemporary interpretation of Chanderi saris and dupattas has had an impact on design innovation of the entire industry- simplification of borders and introducing motifs into Chanderi like cows, parrots, sparrows, monkeys, angels & floral motifs of mogra, roses and marigolds.

Originally Chanderi fabrics were white, or off-white dabbed with saffron, which was used by royalty. Now, the complete spectrum of colours are used and the elegance is enhanced through illusionary shades in the form of soft palettes. The initial challenge was to explore ways in which colours of chanderi saris could still make sense in today’s day and age and so we introduced a palette of new colours and colour blocking with yellow, lime green, midnight blue and sharbati pink, which had never been seen before in Chanderi. Importantly, we worked with techniques to fix dyes permanently in the town of Chanderi which is located on a rocky belt where water is scarcely available—so dyeing processes would get hampered. The saris would bleed heavily, and it was even said that if a woman got caught in the rain wearing a red sari, she would turn red herself.

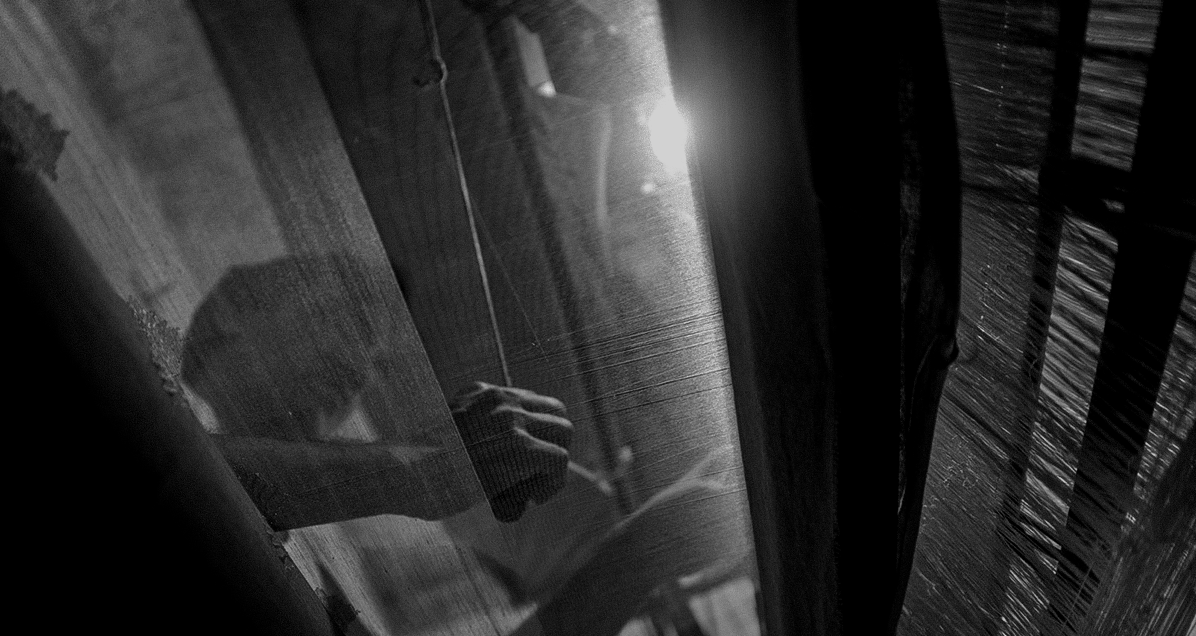

Our designs and motifs are first hand drawn and converted into a naksha (blueprint), which is seeded into a jaala. This jaala technique still exists in Chanderi weaving even though it became extinct in Benarasi looms nearly 80 years ago. They use a wooden instrument called an ‘ankhda’ to manage the jaala and start weaving. In the 30 or 40 villages surrounding Chanderi where the weaving is done, the entire family helps out with the production; they fill the shuttle which is then put into the weft. The last component is the zari, which is mainly used in the border and for filing motifs; it comes from Surat and Benares. Chanderi saris aren’t washed after weaving traditionally, but at Raw Mango, we soften the saris to give them a better hand feel. In terms of the time taken to weave, it depends on the complexity of the sari. A Chanderi sari with a plain weave will take approximately three days, but depending on the level of detail in the design, it can be up to 15 days.

We have worked with the same weavers for over a decade, at the start of which the loom strength in Chanderi has increased from 3,500 to 5,000, and a sphere of influence has been created. Now, consumers speak about Varanasi and Chanderi in one breath. Since then, the average weaver wage has increased fivefold. The Scindia family- who have unconditional love and patronage for the craft- were responsible for bringing infrastructure, such as electricity and water to various villages in the region.

“I’ve always seen my relationship with weavers as collaborators, because frankly, weaving is in their heritage and their DNA. They could do things with their eyes closed and at the end of the day, I’m an outsider. Perhaps I look at things differently, and they may not see what I see. But our respective growth comes from the combination of both.”

- Sanjay Garg